Cheese making is essentially a dehydration process in which milk casein, fat and minerals are concentrated 6 to 12-fold, depending on the variety. The basic steps common to most varieties are:

- acidification

- coagulation

- dehydration

- salting

- ripening

(Common steps to most cheese making processies. From: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/42344)

(Common steps to most cheese making processies. From: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/42344)

Acid production is the major function of the starter bacteria. Lactic acid is responsible for the fresh acidic flavor of unripened cheese and is important in coagulation of milk casein, which is accomplished by the combined action of rennet (an enzyme) and lactic acid produced by the microbes. During the ripening process the bacteria play other essential roles by producing volatile flavor compounds (e.g. diacetyl, aldehydes), by releasing proteolytic and lipolytic enzymes involved in cheese ripening, and by producing natural antibiotic substances that suppress growth of pathogens and other spoilage microorganisms. For Cheddar and Colby cheese production, starter cultures include strains of Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris and/or lactis. Likewise, blue cheeses require Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris or lactis, but the mold Penicillium roqueforti is also added as a secondary culture for flavor and blue appearance.

Overview of cheese production

Coagulation

During coagulation, modifications on the milk protein complex occur under defined conditions of temperature and by action of a coagulant agent, which changes the physical aspect of milk from liquid to a jelly-like mass. Various coagulants are available, e.g. lemon juice, plant rennet or more commonly a proteolytic enzyme such as chymosin (rennin) or – due to high demand from the cheese industry - proteolytic enzymes from the mould Rhizomucor miehei obtained via biotechnology. These enzymes have an acidic nature, meaning they have optimum activity in a slightly acidic environment. Therefore, the action of LAB in this phase is crucial as they are required to rapidly release enough lactic acid, to lower the milk pH from 6.7 to near 6.2, (thus creating an appropriate environment for optimum activity of rennin) and later to pH 4.5 as the processing proceeds, creating an inhospitable environment for many unwanted bacteria, thus increasing the end product safety.

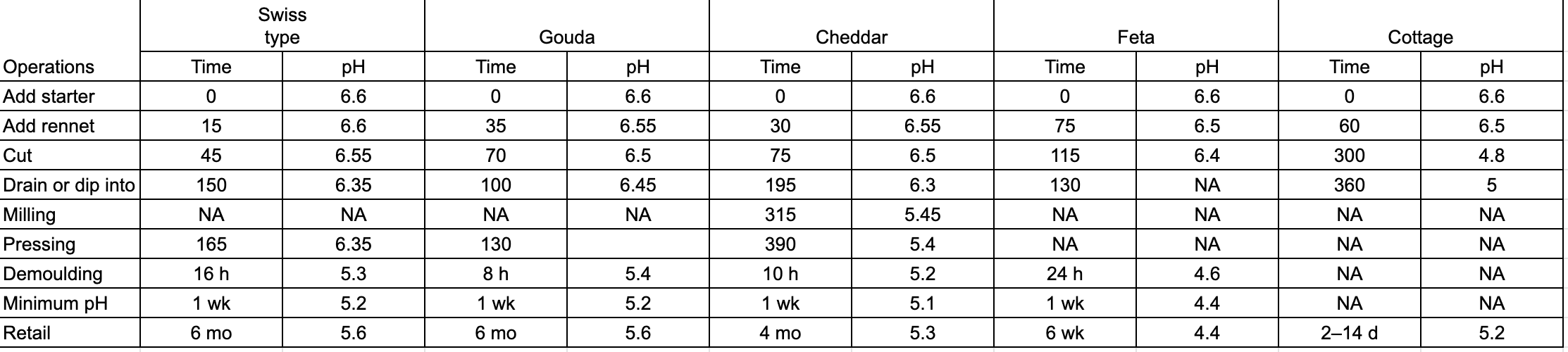

(Typical pH vs time profiles for several cheese varieties (time is in minutes unless otherwise noted). Adapted from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/42344)

(Typical pH vs time profiles for several cheese varieties (time is in minutes unless otherwise noted). Adapted from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/42344)

Cutting the coagulum

The resulting coagulum may be cut with appropriate knives into curd particles of a defined size, e.g. 1–2 cm, or it may be transferred into containers or cheese moulds. The cutting or ladling of the coagulum is a very important step in the manufacture of some cheese varieties as it determines the rate of acid development and the body (firmness) and texture of the cheese.

Heating or cooking the curds

Heating (37–45 ºC, depending on the type of cheese) the curds and whey affects the rate at which whey is expelled from the curd particles and the growth of the starter microorganisms. During heating, the curds and whey are often stirred to maintain the curd in the form of separate particles.

Whey removal

After heating and stirring, and when the curd particles have firmed and the correct acid development have taken place, the whey is removed allowing the curd particles to mat together.

Salting and milling the curd

In cheeses such as Cheddar, when the curd has reached the desired texture, it is broken up into small pieces to enable it to be salted evenly. Milling the curd can be done either by hand or mechanically. Salting is usually done to enhance the taste of the curd and to increase its safety and shelf life.

Ripening

Finally, for most cheeses, the resulting mass is molded and put to ripening for periods that may vary from 15 days to one, two or more years. Ripening is a slow phase, crucial for the development of aroma and flavor, brought about by the action of the many enzymes released by LAB. During ripening the protein in cheese is broken down from casein to low molecular weight peptides and amino acids. Proteolysis is the major – and certainly the most complex of biochemical events that take place during ripening of most cheese varieties and LAB play an important role in it. This happens while the cheeses are stored in the curing cabinets and in some cases in caves, usually with temperature and humidity controlled

Flavour compounds in cheese

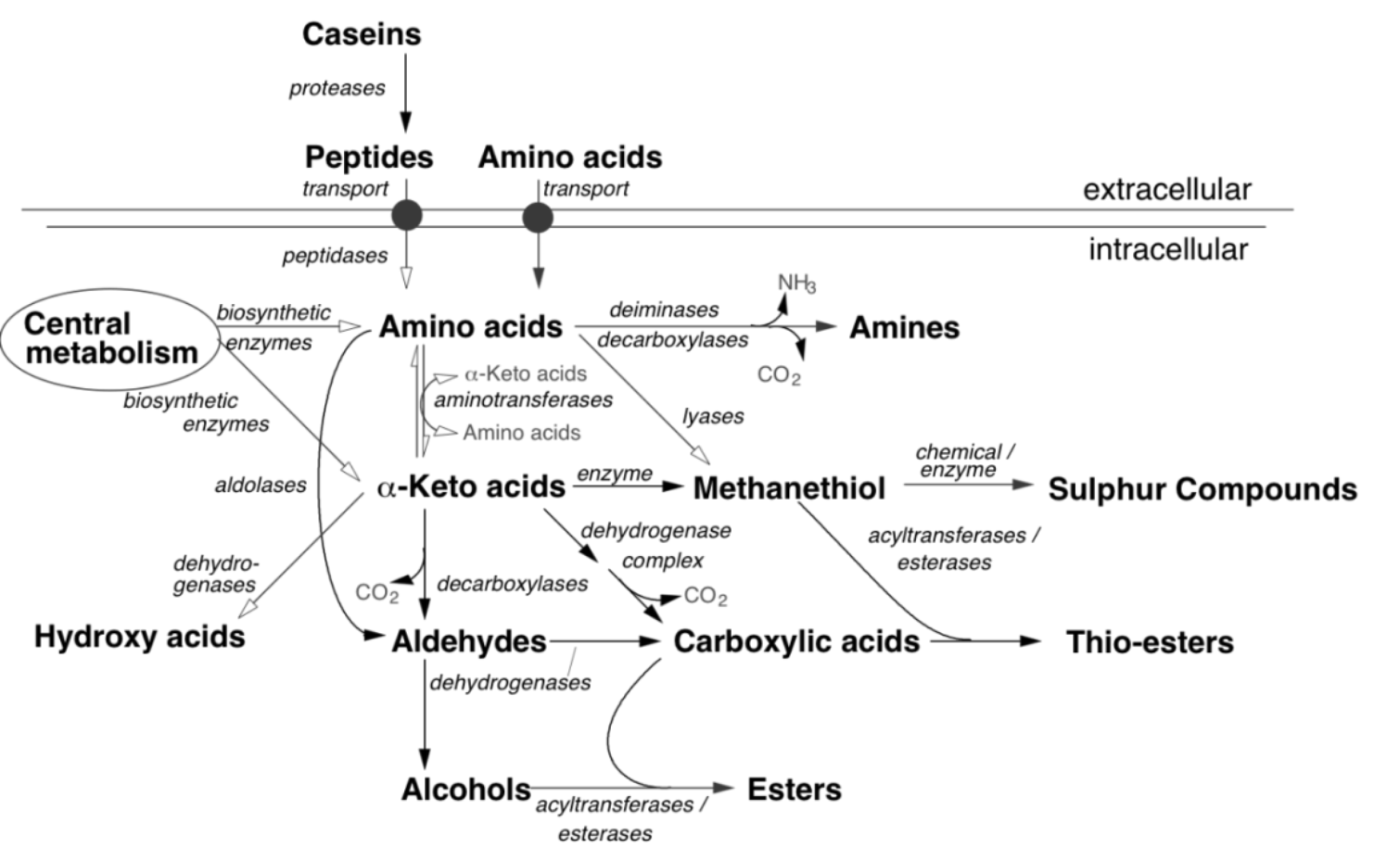

(General pathways leading to intracellular meatabolites, and their degradation routes to potential flavour compounds. More specifically, pathways from methionine to flavour compounds (methanethiol, thioesters, sulphur compounds) are shown (Adapted from Kranemburg et al., 2002). From: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/42344)

(General pathways leading to intracellular meatabolites, and their degradation routes to potential flavour compounds. More specifically, pathways from methionine to flavour compounds (methanethiol, thioesters, sulphur compounds) are shown (Adapted from Kranemburg et al., 2002). From: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/42344)

Cheese cultures

Lactobacillus and Streptococcus species are used as thermophilic starter cultures.

Lacticaseibacillus, Lactiplantibacillus, Ligilactobacillus and Limosilactobacillus species are major representatives of non-starter LAB.

Sources

- 2012, Kongo. Lactic Acid Bacteria as Starter-Cultures for Cheese Processing: Past, Present and Future Developments https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/42344