It seems like (at least online) there are two camps arguing with each other what the best course in the fight for climate change is: personal action (reducing your own carbon footprint) and collective actions (i.e. governmental policies and big systemic changes in industries). I never understand how these two are mutually exclusive, and why people argue about what is more important. They are both equally important and don’t work without the other!

Personal action is often regarded as having too little or even no impact. But that argument seems to be a way for people to absolving themselves from responsibility and power. Often grounded in envy, greed and self-defence - Why should I stop flying when there are billionaires flying to space? Why should I feel bad about eating meat when this guy over there is eating double my portion? - things that are (unfortunatley) deeply human. And I can totally understand it, because I’m not immune to these thoughts either. It’s not nice to on one hand become aware of your bad impact on the environment, feel like you want to change it, feel guilty about things that you can’t or don’t want to change, and then see others not care while you try to make an effort.

The way out of this (at least for me) is to reframe these personal actions as something positive. Not consuming so much has had a very calming effect on life in general (is shopping really fun??). It’s cheaper, and not accumulating so many things is quite relieving. Eating vegan and vegetarian has improved my cooking, made me more curious about ingredients and other cuisines, and it’s (usually) healthier. Not owning a car is another huge reliever of the stress that road rage, parking problems, traffic jams, accidents, repairs etc. would cause, and saves me quite a lot of money. I LOVE my calm train commute where I can read a book or look out the window.

And as an argument for people still insisting that personal action won’t change a thing: Industries have forever figured out that tiny actions have a HUGE impact! The famous example of airlines reducing the number or even the weight of paper of in-flight magazines cuts litterally millions of liters of fuel every year. I work in a big food company - just reducing some heating process by one degree in the factory has an enormous impact on total energy consumption (and costs) as well as some knock-on effects like less wear on heat exchangers (i.e. cost savings), less need for harsh cleaning materials (i.e. positive for the environment), etc. It’s so short-sighted to think that none of us individuals has an impact.

Here’s another article that argues that personal action doesn’t have much impact and that people shouldn’t be too preachy about it: https://medianism.org/2022/08/15/you-cant-get-no-satisfaction-from-reducing-your-own-personal-carbon-footprint/

I do agree with the premise:

Being self-righteous about your own personal actions against climate change can make other people feel inferior and cause them to reject the entire idea.

Our most important job as environmentalists is to convince the people who haven’t yet been convinced that we should do anything at all.

But that doesn’t mean that working on reducing your own personal footprint is pointless. Sure, it’s much more important to work on collective reduction in carbon emissions than to fret about a piece of cheese you ate or a pair of trousers you bought, but who if not WE AS CONSUMERS should stop consuming? Fewer things being needlessly produced, fewer things being shipped around the planet, fewer things ending up in landfills and oceans. It’s always presented as such a sacrifice, but I think many people (in rich countries) could live an equally happy, if not happier, life if their focus wasn’t so much on accumulating things and spending money on status symbols.

The more interesting point in this article is:

There is an asymmetry between the efforts of climate-change environmentalists versus big carbon. Environmentalists spend a lot of our moral resources to increase our personal moral purity and reduce our individual carbon footprint. On the other side of the political divide, big carbon doesn’t waste any resources on personal moral purity and so they can devote all their resources to influence the public sphere to stop policies that would actually make a difference.

Not so much the thing about personal moral purity etc. (the article spends far too much space painting environmentalists as these ultra-preachy people who feel superior). But the idea that industries (oil, plastic, sugar, cigarettes, cars, etc.) encourage putting the onus on individual people as a distraction, while spending their time and power on influencing policies and politics.

It’s not a strategy that environmentalists should or could adopt - Big Oil makes a LOT of money and has interest in making even more, on the other hand environmentalists are not driven by profit and can’t (and shouldn’t) offer the same incentives to (corrupt) politicians as oil lobbyists do. But it’s important to identify these strategies and call companies out on them. Investigate, reveal, explain, publicize.

Overall, I agree that if you want to have maximum positive effect on the climate, it’s much better to look for actions with the most impact, participate in organisations and events, be vocal about climate change and be inclusive and not alienating about it, than to just reduce your own personal carbon footprint. But again, how is anything supposed to change if no one is making ANY change? Many drops make an ocean. We need both - personal action and collective action. One doesn’t work without the other, it’s a chicken and egg problem.

Actions

- Find impactful and public climate actions (including: donate to and support the actions that have the most impact).

- Be vocal about participating in (fun) climate actions.

- Show the upsides of leading a low-carbon life style. It’s not a sacrifice: not owning a car is freedom; train travel is fun, cheap and fast; repairing clothes is often more rewarding than buying new ones; vegan food is delicious and healthy; hobbies don’t have to cost money or be based on consumption.

- Expose industries for their distracting actions as well as their damaging actions (car companies producing ever bigger cars and marketing them as FREEDOM; companies implementing distracting “skip the straw” initatives while collaborating with oil industry, etc.).

What makes people care

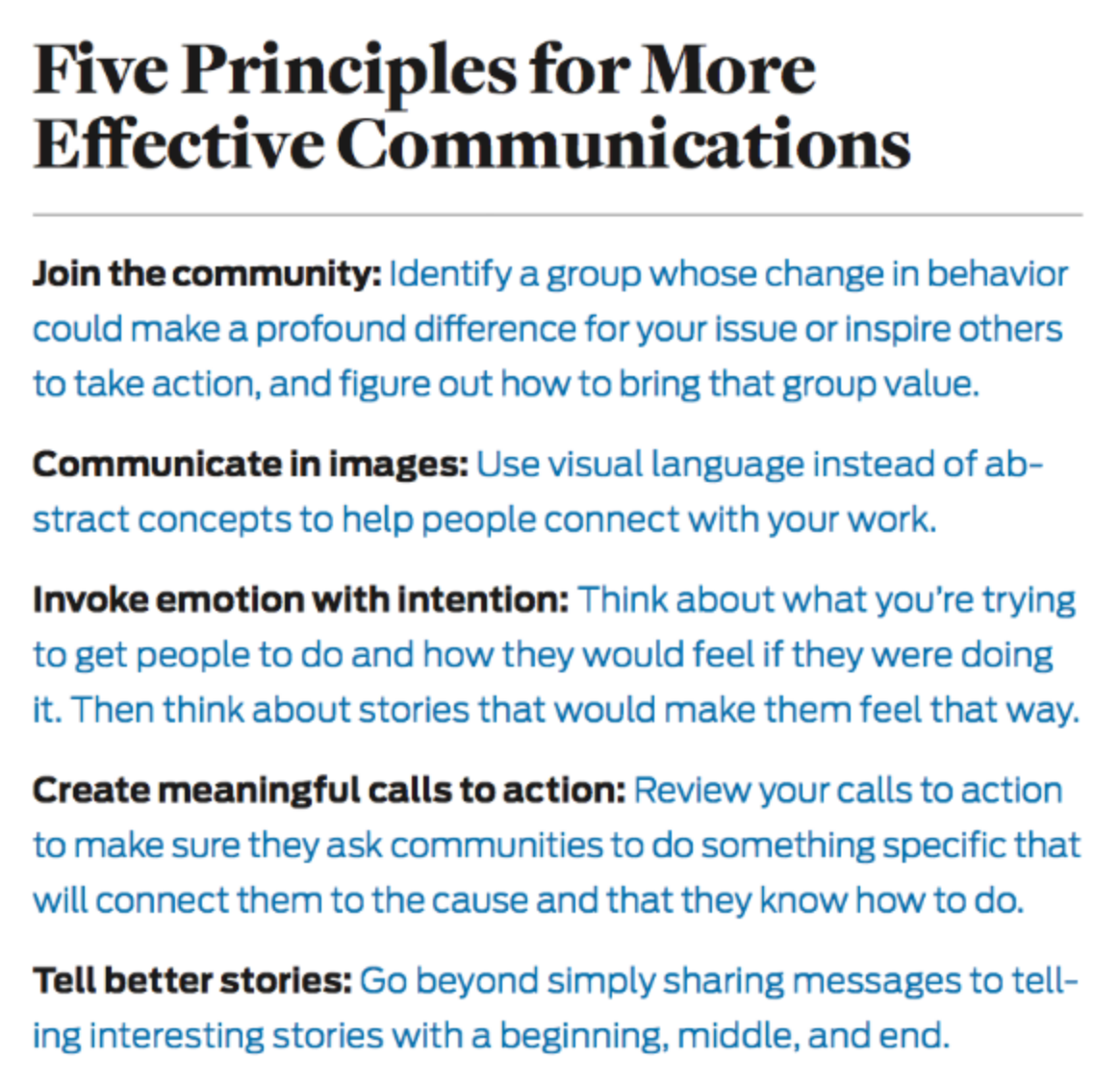

(from The Science of What Makes People Care)

Research from multiple disciplines tells us that people engage and consume information that affirms their identities and aligns with their deeply held values and worldview, and avoid or reject information that challenges or threatens them.

And very importantly:

People seek information that makes them feel good about themselves and allows them to be a better version of themselves. If you start with this understanding of the human mind and behavior, you can design campaigns that help people see where your values intersect and how the issues you are working on matter to them.

People tend to avoid or remain unmoved by stories and situations that attempt to make them feel bad. They avoid information that makes them feel sad, fearful, or guilty when there isn’t a way to resolve those feelings.

On the other hand, very powerful emotions are awe (e.g. at the beauty of nature) and pride (e.g. about helping the environment).

Effective calls to action follow three rules:

- They are specific

- The target community sees how the solution will help solve the problem

- And they are something the community knows how to do.

Calls to action that leave people feeling that they will not make a difference on the issue will likely result in inaction.

People fail to act not because they do not have enough information, but because they don’t care or they don’t know what to do. If you start with this perspective as the foundation for your work, you can craft a strategy that helps people care and tells them exactly what you want them to do.